San Antonio Palopó Photography

Perched on the edge of Lake Atitlán is a town without time.

Published: by PICSPORADIC

San Antonio Palopó

At the end of the precarious one-lane paved road from Panajachel is the small town of San Antonio Palopo. Isolated in geography and tradition, its largely indigenous population work the land and in the waters of Lake Atitlán.

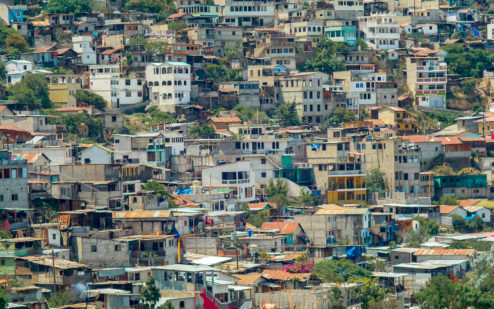

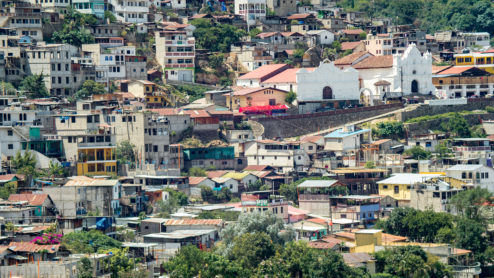

The first time I saw San Antonio I was awestruck. The town is a contiguous structure of concrete block and wire – simple homesteads and livestock- intertwined by tight alleyways and rusty tin roofs climbing the mountainside above the lake. The locals carry provisions on their heads up steep steps to cliff dwellings which seamlessly integrate with terraced fields of onions, the local crop.

The first time I saw San Antonio I was awestruck. The town is a contiguous structure of concrete block and wire – simple homesteads and livestock- intertwined by tight alleyways and rusty tin roofs climbing the mountainside above the lake. The locals carry provisions on their heads up steep steps to cliff dwellings which seamlessly integrate with terraced fields of onions, the local crop.

An incredible contrast of beauty and poverty

Through my work with Mayan Families my understanding of San Antonio changed greatly. It wasn’t until I got up close with the people there that I realized just how marginalized the population had become. During hurricane sandy in 2012 the town lost its only school in a landslide – since then there has been no aid on the behalf of the government to rebuild the school. The school was necessary for many reasons. The people of San Antonio speak Kaqchikel and without lessons in the spanish language an entire generation is growing up without the tools to communicate and work outside of their community.

Rooted in tradition – Farmers work the steep hillsides above Lake Atitlán.

Cebolla

Acres of onions

Everyone San Antonio grows up working the fields. The terraced plots of land stretch upwards from the town joined together by irrigation ditches and small plastic pipe; the lifeline of water in this dry region of Guatemala. The main crop of the town is cebolla or onions.

The onions are sold clean which involves a tremendous amount of work and water. Most children begin work when they can walk, and can be seen working alongside the elders in the fields. There is very little work in San Antonio, everyone grows onions. It’s their only crop.

Many of the Mayan farmers are suffering from the low prices they receive for their crops. Once a month the large trucks come to town to pick up the harvest. The farmers heave their heavy sacks of produce on their heads walk the steep paths down from the fields to market. At the truck there is an on-site bidding war and once the truck is full the driver leaves. The cheap produce bound for the capital of Guatemala city and eventually the United States of America.

Gregorio

I met Gregorio on my photo hunt mountains above the town. His plot sits at a cliff overlooking all of San Antonio and as I set up my tripod he came up to me. Gregorio seventy years old and walks up to the terraces each day where he grows onions and a bit of Marijuana. He spoke just enough Spanish to tell me a bit of history about the lake, his family and the town where he has been living his entire life.

Two months ago his eldest left for the United States, crossing the border illegally in a dangerous 40 day journey. His son now lives in new York where he works in a kitchen. He will most likely never return to his beautiful homeland in Guatemala. The old man and I sat for about an hour, both of us chatting in our broken spanish and taking in the amazing view of Lake Atitlán.

The construction continues perpetually. Each man working tirelessly to weave his piece of the giant puzzle of San Antonio with cement and block.

Houses on top of houses on the steep hillside.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.